How a renowned American-built yacht helped set the stage for the end of World War II.

By L. Dougles Keeney

On January 23, 1942, just six weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy purchased the yacht Delphine and put her into dry dock in River Rouge, Michigan, not far from the family estate of Horace Dodge, the automotive titan who had her built. Delphine was not the only yacht so acquired. In a crash program to beef up America’s impoverished fleet, the Navy acquired scores of hulls, but the 258-foot steam yacht Delphine alone was destined for immortality.

Fast forward to November 1943. Adolf Hitler’s grip on continental Europe had scarcely been weakened by costly aerial bombing. Combat in the Pacific was bloody and slow. Main Street America was reeling from war deaths and injuries, and the Allied leaders were stalled by a bitter divide over the war strategy to defeat Germany. Along with Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had concluded the only way to bridge the divide was to present the American plan (D-Day) and the British plan (invade the Greek Islands) to Joseph Stalin and let the Soviet marshal decide. The pivotal meeting of Allied leaders was set for the Iranian capital of Tehran.

The plan was for FDR to board the battleship USS Iowa in the Chesapeake Bay for the voyage across the Atlantic to Algeria, where he would board a plane and fly to Egypt, and then another plane to fly up to Tehran. The 6,700-mile journey would unfold in four perilous legs, each to be conducted in utter and absolute secrecy lest it all fall apart from the beginning.

“Those of us who had to do with the planning for this expedition were very conscious that the president was running grave personal risk in such extensive travel by sea and air,” said FDR’s naval aide, Lt. William M. Rigdon, “because we believed that, if the enemy could learn of his whereabouts, they would spare no effort to attack by air, submarine or assassin.”

The Need for Secrecy

FDR decided no one should know of the trip lest there be leaks—no newspapermen, no friends of the family, no members of his own cabinet, not even Congress. Rather, he would sneak out of the White House under the cover of darkness, board his special train in Washington, D.C., and be taken down to Newport News, Virginia, and transferred to the Iowa.

Except to a nautical man, it made no sense.

John L. McCrea, captain of the Iowa, was on patrol off Newfoundland when he was ordered to return to the Norfolk Naval Operating Base to ferry Roosevelt across the Atlantic. When briefed on the plan, he had second thoughts: “I was standing out there on deck, and I thought, everybody—Admiral [Royal E.] Ingersoll, Admiral [Ernest J.] King, the president, everybody that I have talked to—has said that this is a very secret mission. But if the president catches a special train and goes to Newport News, everybody in tidewater Virginia is going to know what’s going on.

“All of a sudden it occurred to me,” said McCrea. “Why can’t I come up here and meet him at the mouth of the Potomac, get him on board ship and all the rest of these people? We can get down by 6 o’clock that night, fill up with oil. The tide serves about 11 o’clock, and it will be high water and I can go on to sea.”

McCrea sent for his navigator. They looked at the charts for Chesapeake Bay, and sure enough it seemed to work.

“The president could come down to the mouth of the Potomac on his yacht, the Potomac, and that would be the end of it. The only people who would know that he was leaving Washington at all would be the people there at the naval base and also the people at the Navy yard.

“Admiral Ingersoll looked at me, and he said, ‘I approve. Take my plane and go back to Washington right now.’ I got on the plane and away I went. I went in and saw Admiral King. He said, ‘I approve. Go to the White House and see the president.’ I did, and the president said, ‘I approve.’ And that was it.”

But that wasn’t it. The president might easily slip out of Washington on the Potomac, but his cover story wouldn’t last if the rest of his party were outed. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and their senior admirals and generals had to get to Tehran too. Thankfully, a second yacht was available: King’s flagship, the USS Dauntless, better known to yachtsmen as the Delphine.

From Yacht to Warship

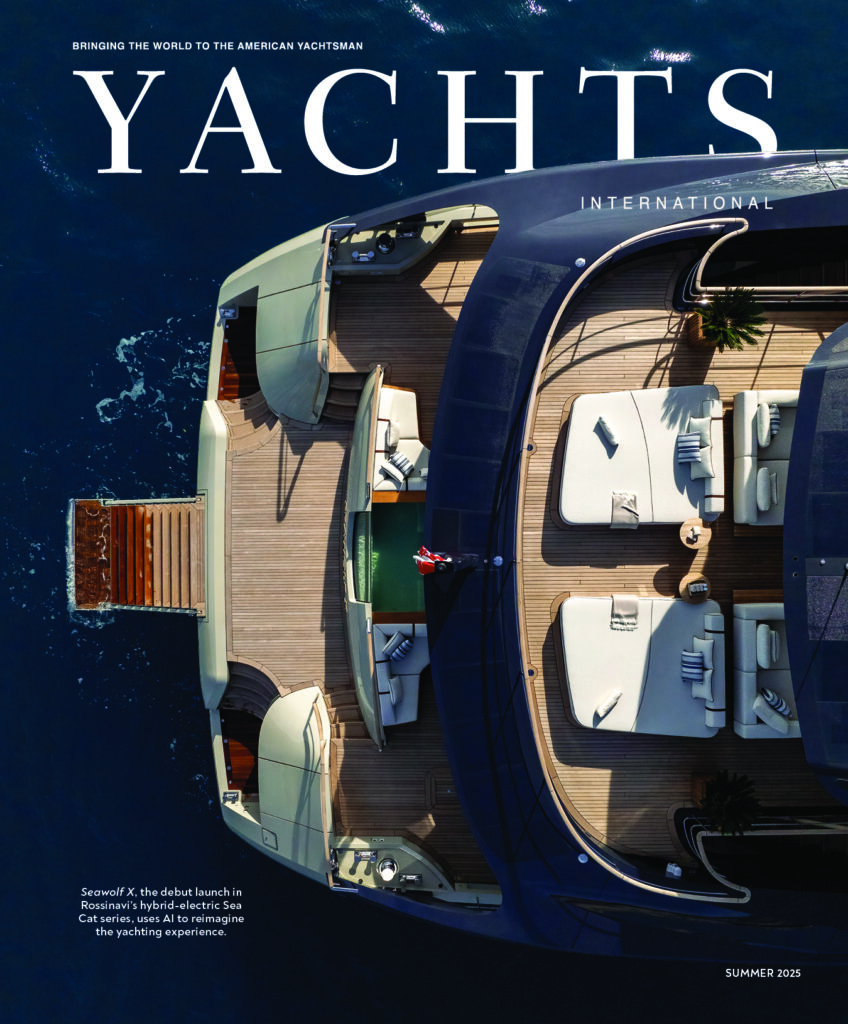

When war broke out in 1941, ships were urgently needed and few were better qualified for service than Delphine. She was one of the biggest yachts of her day and could sleep 50 sailors and carry 20 guests in handsome staterooms, many with en suite heads. Her volume, thanks to a 35-foot beam, made her ideal as the floating command post for King.

She was gutted after the Navy acquired her in January 1942. Large, panoramic windows in her hull were replaced with portholes. Much of the boat deck was ripped out to accommodate six self-launching liferafts, and the aft promenade deck was cut away for an anti-aircraft gun. The superstructure was extended forward some 10 feet to accommodate more crew bunks, and .50-caliber machine guns were added, six in total. New masts were installed, one with new radar. A larger searchlight was placed on top of the pilothouse.

Inside the hull, the dining room became a radio room, pantry and officers’ wardroom. The guest staterooms on the lower deck were subdivided into 10 smaller officers’ staterooms. The ship was wired for electricity, and air conditioning was installed.

To complete the conversion, Delphine was dipped in the colors of war—gray/green/blue camouflage paint—and designated Naval Gunboat PG 61 (patrol gunboat), the USS Dauntless. Dauntless arrived at the Navy Yard on June 16, 1943, and was moored to Pier 1. On June 17, King’s flag was broken and he moved aboard.

Enter Dauntless and a Ruse

To make McCrea’s plan work, Dauntless had to take 19 members of FDR’s War Department down the Potomac to the USS Iowa in the Chesapeake Bay. Foremost among those passengers were the commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Force, Henry A “Hap” Arnold, Army Chief of Staff and future Secretary of State General George C. Marshall, King and 16 of the senior-most admirals and generals in the Pentagon.

At 8 a.m. on November 11, 1943, on a cold, rainy, windswept morning, sailors heaved Dauntless’ lines and the captain ordered the ship to make way. With the yacht’s triple-expansion steam engines turning, the conning officer eased Dauntless away from the pier and into the Potomac with her bow pointed downstream. Her guns were manned, although the smell of coffee perfumed the air and a buffet of breakfast delicacies was set out in the salon.

With Allied spies in every port, Dauntless was as rich a target as any, and for those aboard her, it was a painfully slow voyage—eight hours to go just 100 miles. But at 4 p.m. it was over, and no one was the wiser. Dauntless hove into view as she rounded the mouth of the Potomac and came alongside the Iowa. The Iowa’s accommodation ladder was lowered from its davits, and the tedious process of transferring men and luggage began. McCrea greeted each of his guests and had an officer waiting to take them to their quarters. Because they would be traveling in a war zone, they were also assigned battle stations.

Closing the Circle

Dauntless did her job admirably, but the job was only half done. At 9:30 p.m., as she turned around and headed back upriver, the president left the White House for the Marine Corps base at Quantico, Virginia. Behind him, a gust of wind blew open the flag that flew over the White House to indicate the president was still in residence, part of the ruse to explain Roosevelt’s absence to the press—that he was merely taking a short vacation cruising on the Potomac. The president’s motorcade drove down the rain-slickened roads and passed through the gates of the Marine Corps base and out to the docks with only the base commandant knowing what was going on. The president was lifted onto the Potomac—built in 1934 in Wisconsin as a Coast Guard cutter and converted to serve as Roosevelt’s presidential yacht in 1936—and went right to his stateroom and was fast asleep. The Potomac gunned her engines and swung out into the stream. To her starboard, the Navy submarine chaser SC-664 cast off her lines and pulled abeam, and together they churned the brownish river into a soft boil and headed downstream as armed lookouts and Secret Service agents scanned the dark banks for anything suspicious.

“During the night we passed and exchanged calls with the USS Dauntless and the USS Stewart, bound upriver for Washington,” wrote Rigdon. “They were returning there after having transported members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff party and their baggage to the Iowa.”

Some five hours later, at 3:30 a.m., they pulled over to the side of the river and came to a halt. “The Potomac anchored off Cherry Point, Virginia, near the mouth of the Potomac River, to await the transfer of the president and his party,” wrote Rigdon in his final entry for the night. “Some five miles distant, farther out in the bay, the massive Iowa could be seen riding at anchor.”

And there they waited for dawn.

“At 15 minutes before 9, the tiny, white presidential yacht Potomac hove into distant view,” McCrea recorded in his diary as he watched approvingly.

Rigdon remembered: “At 9:16 a.m., the president went aboard the Iowa, using his special brow which was rigged from the after sundeck of the Potomac to the main deck of the Iowa, just abreast of the Iowa’s number three turret. At his request, no honors were rendered as he came on board the Iowa.”

Instead, Roosevelt extended his hand and greeted the captain. “It’s good to see you again, John,” he said. McCrea responded in kind.

Thus began the journey to what the world would come to know as the Tehran Conference, a meeting held some 71 years ago, the first-ever meeting of the Big Three, a meeting that set the stage for the defeat of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

Douglas Keeney is the bestselling author of more than a dozen books on American history. His most recent book, “The Eleventh Hour,” chronicles Roosevelt’s journey to Tehran and the behind-the-scenes negotiations that paved the way to D-Day.

For information about visiting the USS Iowa in Los Angeles, go to: pacificbattleship.com

For information about visiting the USS Potomac in Oakland, California, go to: usspotomac.org

Delphine is for sale. For information, email: [email protected]