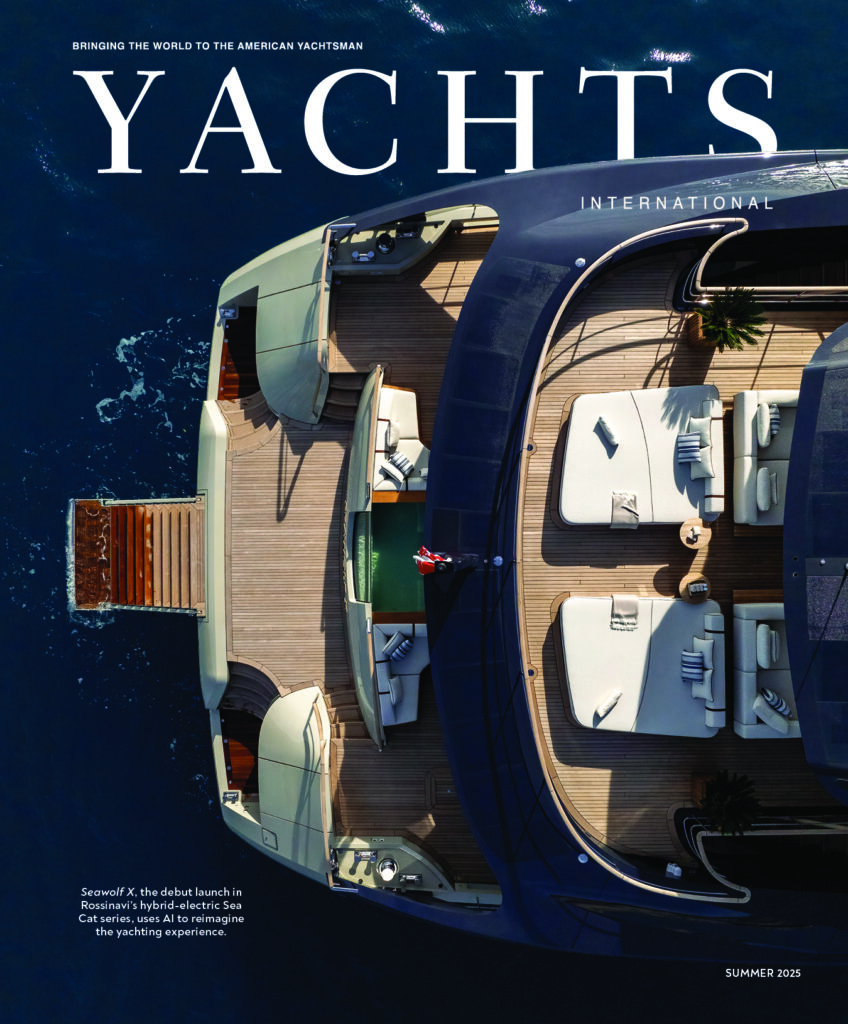

The Astondoa 72 GLX showcases the Spanish yard’s custom yachtbuilding prowess.

By Kevin Koenig

One typically bright and sunny afternoon in Coconut Grove, Florida, Rafael Barca walked the decks of the Astondoa 72 GLX with a barely perceptible limp, making droll and insightful comments here and there with a voice that rumbled like a big diesel engine. As president of Flagship Marine Group, Barca was in charge of my tour of the boat and, frankly, I couldn’t think of a better person to do it. The man is large and well-built without being bulky, rugged without being graceless. It was clear from his carriage and demeanor that Barca had some stories to tell—and he’d tell all of them in a rolling Cuban accent. Indeed, in more than a few ways, Rafael Barca seems to be the human embodiment of the Astondoa 72.

Astondoa Yachts is a Spanish company founded nearly a century ago. Over the years, it has splashed almost 4,000 boats, some exceeding 200 feet in length, and yet, you could be forgiven if you’ve never heard of the company. It is not as common a name as some of its competitors—the Sunseekers and Azimuts of the world. And somewhat counter intuitively, the company is proud of its relative anonymity—it means Astondoa doesn’t spend a heck of a lot of money on marketing and advertising, feeling that money is better put back into the boatbuilding process. Though Astondoas are priced commensurately with Sunseeker and Azimut, the company doesn’t really see those brands as competitors. Astondoa believes it builds a higher quality boat for the same price as those companies because it doesn’t use any middlemen for its components.

For example, Astondoa owns the largest furniture company in Europe. It builds a lot of furniture for custom homes—like castles. Really. That same furniture goes into its boats. Astondoa owns its own 5-axis CNC router and can build a 90-foot mold in-factory. It has been stockpiling Burmese teak for more than 20 years. Astondoa, in effect, has figured out how to control the means of production.

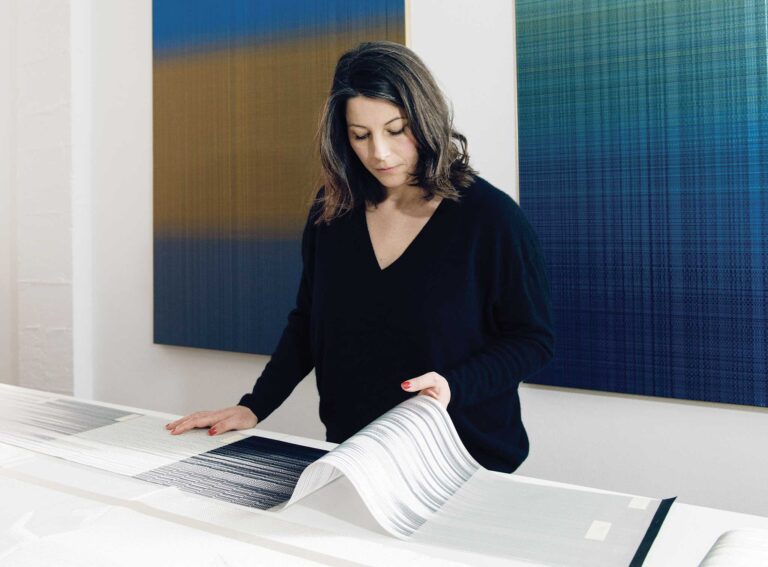

What’s more, Astondoas are fully custom. For every Astondoa built, the designer Cristiano Gatto will sit down with the owner and go through every aspect of the boat with him. If the owner isn’t quite sure what he wants, Gatto is happy to offer some expert guidance. Once a plan is agreed upon, Astondoa produces a rendering in photographic detail. Then, the Astondoa workforce, which averages about 25 years on the job, gets to work.

To review: venerable company, owns all its stuff, experienced workforce, fully custom, promises a good bargain. All of this is well and good, but it means nil if the end product isn’t up to snuff. So how about the 72 GLX? She’s a little bit boxy at first glance. But that aesthetic tradeoff manifests itself in other areas that, for my money, more than makes up for anything lost. Like, for instance, the 6-foot 10-inch headroom that pervades the main deck.

Another area with a surprising amount of space was the engine room, which I accessed through a fairly tight entryway beneath the bridge-deck stairs. Once I popped through that little rabbit hole, though, I found myself in a true engine room, to the tune of about 6 feet 3 inches of headroom. It certainly gave the beastly twin 1,224-horsepower MAN CV common rail diesels enough space to breathe. The area was well vented, so if you happened to find yourself down there doing some repairs, you could breathe too.

Above the engine room is a cockpit that is fully shaded by the flybridge (more on that in a moment). Moving forward, I noticed the cockpit sole is fully flush with the sole of the salon. This is a design attribute that when first pointed out to me as a novice yacht journalist I kind of shrugged off. But as I’ve progressed, and noticed how rare a thing it actually is, I’ve come to accept it as a harbinger of good design. Because really, with all the weight issues and structural components to consider, if a boatbuilder is deft enough to get everything to fit so that the deck is flat and the customer doesn’t have to step up six inches to get from one area to another, well, usually that builder really knows what it’s doing. I should note, there’s a water-catching grate required by EU rules just abaft the salon so you don’t flood the interior, and that’s a good thing. You wouldn’t want to hurt all that castle-ready furniture or ruin any aspect of the seamless fit and finish with warping. A drawer in the ebony coffee table was so expertly fit that I didn’t even see it until Barca pulled it out to show me.

A galley forward and to starboard was notable for a giant AEG refrigerator and freezer. When Barca opened it to offer me a soda, I legitimately thought the Coke was in a pony can, the interior was so voluminous.

The lower helm was notable for a nice, big windshield with only one central mullion, carbon-fiber accents on the dash and in-house leather work with exemplary stitching. However, when I cranked up the engines and scooted the boat out into Biscayne Bay, I couldn’t help but notice the sightlines were obstructed by extra cabinetry aft and to starboard. When I noted this to Barca, he pointed out that the owners asked specifically for the extra cabinets and weren’t overly concerned with the tight sightlines. “Plus,” he shrugged, “nobody drives down here anyway.” And as I was about to find out, there’s good reason for that.

The aforementioned bridge deck is enormous, and actually bigger than Astondoa’s old 82-foot (25-meter) model’s bridge, since it extends all the way aft to shade the cockpit. The space is covered by a T-top with a canvas sheet that can roll back to let in sunlight as guests see fit. Layouts up top are fully customizable. Mine featured a sun pad forward, two lounges aft and a barbecue and sink. And the helm, well, that really was the place to be.

It was a gorgeous day in South Florida, and as I cruised through S-turns at about 22 knots, I couldn’t help but smile at the boat’s surprising agility, not to mention the way she skimmed right over her not-insignificant wake as I checked out how she might perform in rougher seas than the bay was offering. She got up to a two-way average of 25.4 knots, which is a little pedestrian, but not altogether unexpected for a boat of this size and type. However, her acceleration, particularly from 1,500 to 2,000 rpm, was on point. She jumped from 10.7 to 20.8 knots with just enough giddyup to remind you you’re alive. It’s enough to make you smile. And it was enough to make me not want to hand over the wheel when we were finished.

For more information:flagshipmarinegroup.com or astondoa.es

LOA: 72ft. 4in. (22.05m)

Beam: 18ft. 9in. (5.72m)

Draft: 4ft. (1.24m)

Construction: PRFV /GRP

Displacement (dry): 53.5 tons

Fuel: 1,162 gal. (4,399L)

Speed (max.): 28 knots

Speed (cruising): 24-25 knots

Engines: 2 x 1,224-hp MAN diesels

Engines (optional): 2 x 1,360-hp MAN V12 diesels; 2 x 1,200-hp Volvo Penta diesels w/IPS

Generators: 2 x 21kW Kohler

Water: 400 gal. (1,514L)

Classification: Germanischer Lloyd A

Naval architecture: Astondoa Group

Exterior styling: Astondoa Group

Interior design: Cristiano Gatto

Guest cabins: 2 + VIP and master

Crew: 1 with garage option, 2-3 without garage

Builder: Astilleros Astondoa

Year: 2013